Travel Drawings and Sketches

The Creative Search

The Backstory to The Voyage Le Corbusier: Drawing on the Road

In 2004, I started an on-going journey of travel drawing – a self-imposed education and slow grand tour of sorts. When I set off on my first trip, I had just graduated from Columbia University’s graduate architecture program, where I’d been immersed in paperless studios and new software technologies. Though I took several traditional painting classes while I was there with Gregory Amenoff (and hand drew all studio work in my undergraduate courses at Tulane), I never felt I really knew how to draw in the traditional sense – meaning heading out into the city with my sketchbook and making a representational drawing of a building look real. When most of my friends were anxious to get jobs at top design firms in NYC, I opted to take a trip to Europe to rediscover the practice of drawing on the road.

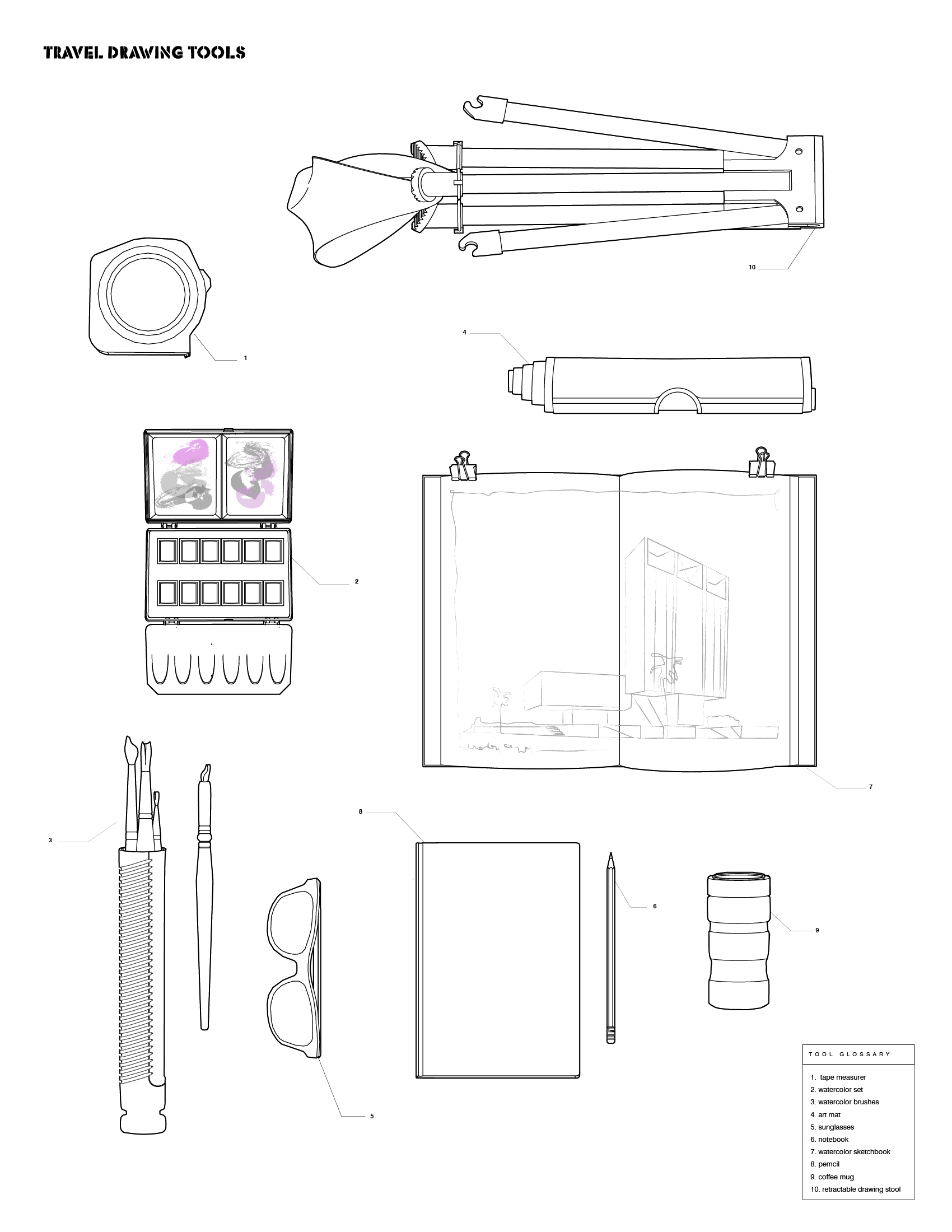

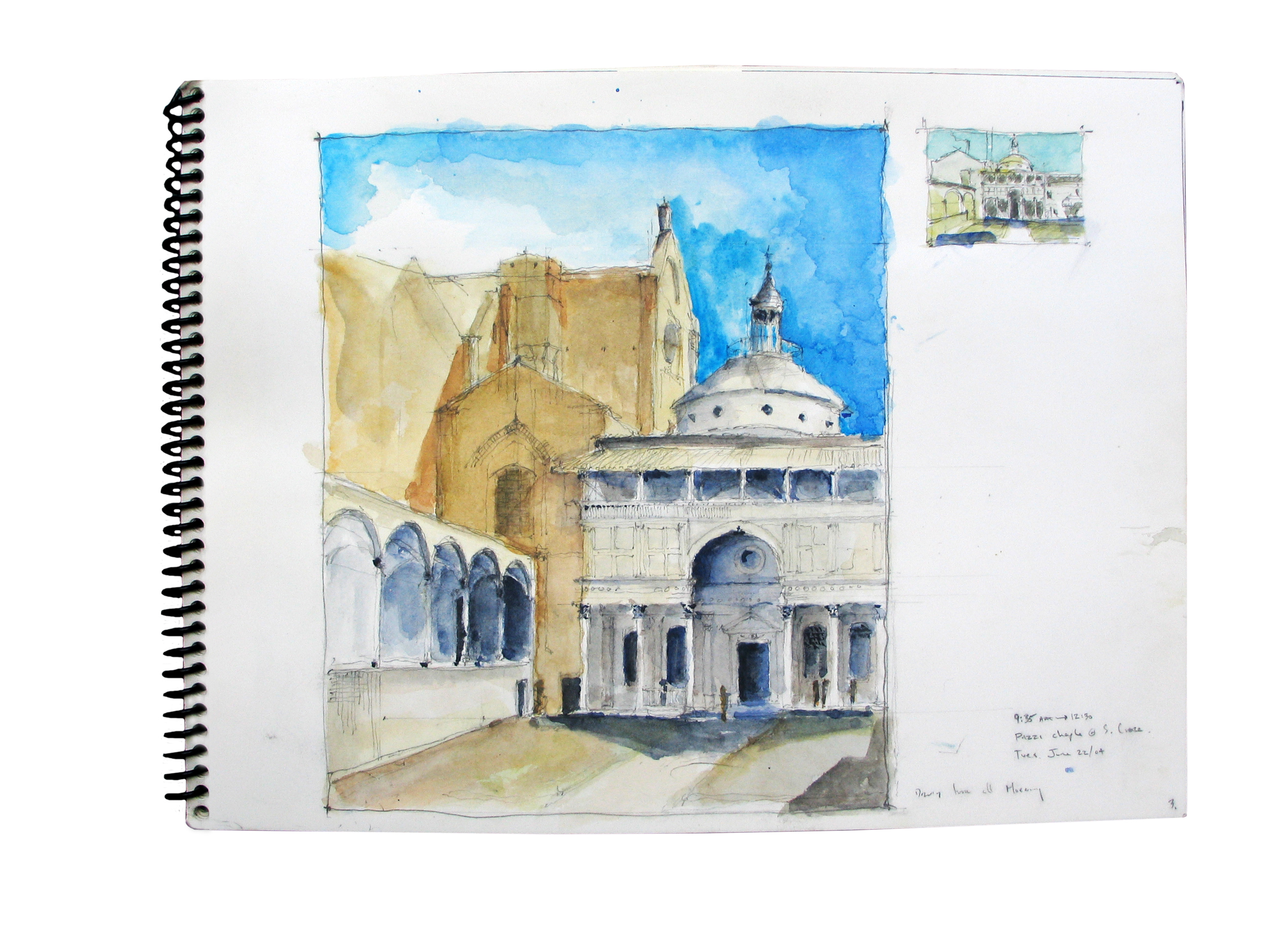

For inspiration, I referenced Le Corbusier’s early travel sketchbooks, which he made between 1907-1911, and ultimately used those as my sole travel guides. On my first trip, I followed Le Corbusier’s itinerary back in 1907 as he traveled through Italy at the age of 19. I committed myself to making two to three drawings a day, producing 65 ‘in situ’ drawings in total, simultaneously studying Corbusier’s drawings of the same subjects in an effort to teach myself how to draw. This experience would spark a series of travel drawing trips in the coming years where I tracked Le Corbusier’s routes across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, creating my own visual toolkit of architectural details, maps, people, buildings, objects, and urban spaces.

Concurrently, the question of “Why draw in the digital age?” has become a great subject of debate within our architectural discourse in the last 15 years. In 2005, just after I began teaching design and drawing at University of Miami’s School of Architecture (including teaching a travel drawing course in the School’s Rome Program), Yale came out with a symposium entitled “Is Drawing Dead?” which addressed the crisis of hand drawing and its place in architecture. As parametric modeling, computational design, digital design and fabrication seemingly promised to hold the future of architecture, hand drawing had come under stress, largely thought to be confining, inefficient and unnecessary in the modern age.

In 2008, Marc Treib came out with Thinking / Drawing, Confronting an Electronic Age, wherein he asked: “Why draw? What role and meaning does drawing by hand play in this digital design-dominated world? How does one enter a creative design project today in architecture school? Is it through drawing or is it through the computer? And in either case, what are the implications of each medium?”

I became particularly interested in this area of research. Notably, I did my undergraduate work and graduate studies between the late 90s and mid 2000s, and realized I belonged to a very unique - and small - group of architects: the only ones who were academically trained in both the analog and digital worlds. While I attended Tulane, we learned architecture through traditional methods of representation (from drawing to model making - using our hands, pencils, paper, scales and rulers). By the time I earned my Masters from Columbia University, the pedagogy had radically changed, wherein the old, analog systems of production were abandoned for a purely paperless studio that solely engaged digital technologies such as Maya, 3ds Max, and Photoshop. Having worked in these two drastically different territories, I learned that each medium has a profound effect on the way in which we draw, design, and understand architectural space and form.

I began analyzing how architecture was advancing because of new digital technologies, and also what was being lost in the absence of hand-drawing. Many of my observations were worked out in an ACSA paper, entitled “Drawing Towards a More Creative Architecture.” Ultimately I argued that digital and analog design tools (i.e. computer modeling and autocad, hand drawing, and physical mock ups) are equally important but the key is to understand when each tool should be used during the design process. I based the argument on neuroscience, my own observations from teaching students for the past seven years; and examples of work from architects who deployed both hand drawing and digital tools in their work – to stress why hand drawing remained critically important.

Amidst this research, The Yale Architectural Press came out with the 41st edition of Perspecta (2008) to talk about travel drawing specifically – looking through the lens of the Grand Tour to understand past, present and future architectural travel. The most interesting take-aways from the journal were the four main questions it posed: Where do we go?; How do we record what we see?; What do we bring back?; and How does this change us?

These questions and discourse ultimately formed the impetus for a book I published through W.W. Norton & Co. in 2016, entitled Voyage Le Corbusier: Drawing on the Road – which collects a compendium of early sketchbook drawings and watercolors by the architect. Having studied his drawings so intensively over the past years, they taught me that we can do something the computer will never be able to do which is draw what “we see.” They show Le Corbusier’s gigantic appetite for travel and visual exploration; looking and drawing to see and to understand in order to know. Meanwhile they reveal how Le Corbusier used his drawing as a method of research and how his drawing process evolved over time, from his initial years of beautiful watercolors to later analytical sketches and shorthand visual notetaking. The subtext of that work is the continued relevance of hand drawing in the digital age, which tends to jettison drawing instruction in favor of computer-based modeling software.

This book, Travel Drawings and Sketches, contains more than 350 paintings, sketches and notes from my travels across Europe and Asia (organized by trip), as well as an essay, entitled “Why Should One Make Travel Drawings?”. This work chronicles my own personal journey and is also an expression of why I think drawing remains relevant in the digital age, not only for students and architects, but anyone who loves drawing and the creative search.

Why Should We Make Travel Drawings?

How do we learn “to see?” How do we learn as architects? How do we come up with ideas? And then once we have these ideas how are they are represented? This quest for learning is always directed towards the ultimate goal – designing and building more meaningful cities. This essay is partially inspired by Professor Marc Treib’s book, Drawing/Thinking: Confronting an Electronic Age. He asks, “Why draw? What role and meaning does drawing by hand play in this digital design dominated world? How does one enter a creative design project today in architecture school? Is it through drawing or is it through the computer? And in either case, what are the implications of each medium?” Treib proffers that “the computer reflects rather than thinks – at least up to this stage in its development, and it can process only what has been entered into its memory by key, mouse or stylus. Electronic processing does not yet substitute for thinking.”

Travel drawings explore the link of research and design and suggest an alternative to subcontracting architectural form making to the parametric processes of the computer. Taken in context of today, this position also debunks the current model of representation –which is most often a seductive digital image with nothing more than curb appeal. The historic investment in the creative search – ie, travel drawing, writing, painting, and exposure to new cultural experiences - reintroduces a back-to-the-basics approach to the process of thinking, observing, and drawing.

The pedagogy of learning to draw and learning through experience is rooted in the long tradition of the Grand Tour. Established in the late 1600’s by the English nobility, The Grand Tour served as a right of rite of passage for every English nobleman, and one that grew out of a curiosity of learning. Thanks to John Locke’s essay, “Concerning Human Understanding” (1690), many believed that knowledge was gained by experiencing the physical world through one’s external senses, and therefore, travel was critical to intellectual development. Architects, like writers, and painters seized upon this idea, taking a standard itinerary across Europe to witness monuments, antiquities, paintings, picturesque landscapes, and ancient cities. Sir John Soane’s travels epitomized the essence of the Grand Tour for the architect. The legacy of his voyage – of the hundreds of drawings made – went on to inspire others such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Gunnar Asplund, Louis Kahn, Michael Graves and Peter Eisenman in the pursuit of “learning to see.”

The tradition of drawing has been a common link between the world’s greatest architects, from Palladio to Le Corbusier to Kahn and Michael Graves, who all proved to be great designers as well as painters. Their creative investigations and starting points for architectural designs were born out of a fundamental knowledge of color and composition. In the case of Le Corbusier, for example, the practice of painting almost every morning channeled the soul and honesty within his theoretical and architectural inventions. Furthermore, in contrast to recent digital creative processes of Rhino and 3ds Max, the great architects of the past drew by hand on site to understand directly scale, light, shadow, and form in full, real life physical three dimensions rather than in the flat virtual two – where there is no sun, no shadow, no gravity, no weight, no material, no scale and zero physical and cultural context. When Peter Eisenman was asked in an interview published in Perspecta 41 how to teach students “to see” he stated, “I am trying to set up a series of case studies to show how Rem Koolhaas moves from Palladio and Schinkel to Le Corbusier to Rem Koolhaas. I am trying to define the persistencies of architecture. What are those things that do not change, what things have changed, where are the fertile areas for change? How do you take the knowledge of Bramante and Palladio and use it in the studio with Zaha Hadid? How does Hadid do it? How does Frank Gehry do it? I want to show examples where masters have been able to take material from a discipline of architecture and manipulate it so it becomes present. How do you produce work that does not rely on graphics or Photoshop or computers, work that relies on the capacity to integrate architectural knowledge into the present?” (Perspecta 41, pg.138) Underlying this line of questioning is the truism that new ideas are always built out of old discoveries, and that contemporary strands of architectural thought are all but a part of a larger connective tissue that forms the discipline itself.

Today, we hear students and even some educators ask: why go to Italy and draw the monuments? We are not going to build in these historical styles again. Should we not go to China or Dubai? What more can be teased out of a drawing Michelangelo’s dome at St Peters again?

Whether you are Le Corbusier working in the swells of the industrial revolution or a global architect today working with Rhino and Max, immeasurable value can be gained in making representational travel drawings, whether in Rome or Dubai. This very basic exercise of examining a subject visually and then documenting it graphically requires one to be able to ascertain the architectural principles that bring buildings to life – i.e. color, composition, form, scale, mass, surface, plan, light and shadow, materials, structure, and context.

Simple representational, on-site, hand drawings force us to analytically decode the building, the landscape, the nature of place. The drawing process is inherently self-informing and self-instructive via the power of reflection. As soon as one puts pencil down to paper one is forced to count sizes, notice sun and shadow, choose and decide -- fast or slow -- about what one wants to emphasize, include, leave out, re-arrange and even distort aspects for what the drawer wants the drawing to say. The immediacy of the onslaught of information as well as decisions on-site is at once over-whelming and exciting. This moment of abstraction ensures new paths for discovery and simultaneously presents infinite avenues for the drawing to inform the author.

While the language of Michelangelo’s dome may not be paramount to current designers, its architectural principles (i.e. form, mass, surface, light, shadow, materials, composition, color, and proportion) exemplify the timelessness of aesthetics in architecture. The medium of drawing allows the exploration of these malleable principles in constant flux, capable of evolution and then re-invention. Classical cities will forever be great laboratories for studying architectural principles. And as Le Corbusier - a young revolutionary – demonstrated, the lessons learned during his early drawing expeditions would go on to form his manifesto. In Towards a New Architecture (1930), which is maybe the most influential book of the twentieth century, Le Corbusier dedicates entire chapters to Mass, Surface, Regulating Lines, Plan, Order, and The Lessons of Rome. These speak to historical and timeless principles – rather than Classical or Modern languages. To this point, even the great architects of today have recognized the value of drawing on the road. In 1960 Colin Rowe sat Peter Eisenman down in front of a Palladian Villa in Veneto and said, “Sit in front of this façade until you tell me something you can’t see. In other words, I don’t want to know about the rustication, I don’t want to know about the proportion of the windows...I want you to tell me something that is implied in the façade.” Eisenman responded later, “ I remember this moment as if it were yesterday. This is how Colin began to teach me to see as an architect. Anyone can look at window to wall relationships, but can anyone see edge stress, the fact the Venetian windows are moved outboard from the center to create a blank space – a void between the windows – which act as negative energy? Such ideas are not found in books. They are found in seeing architecture.” (Perspecta 41, pg. 133) These kinds of revelations are found through real experience and through drawing - all of which are primal to architects and universal to good design.

In the authentic and active experience of drawing – of physically recording what we see – we bring back with us a new way of seeing; we bring back sketchbooks full of information, analysis, and an understanding of architectural principles that will always need to be addressed: color, light, materiality, context, form, mass, profile, shadow, scale, proportion and all the other elements that make architecture matter and affect the human condition. We bring back the understanding of other cultures, history and place, and the emotion, memories, sounds and smells of being in situ. This level of engagement allows us to see and see again.

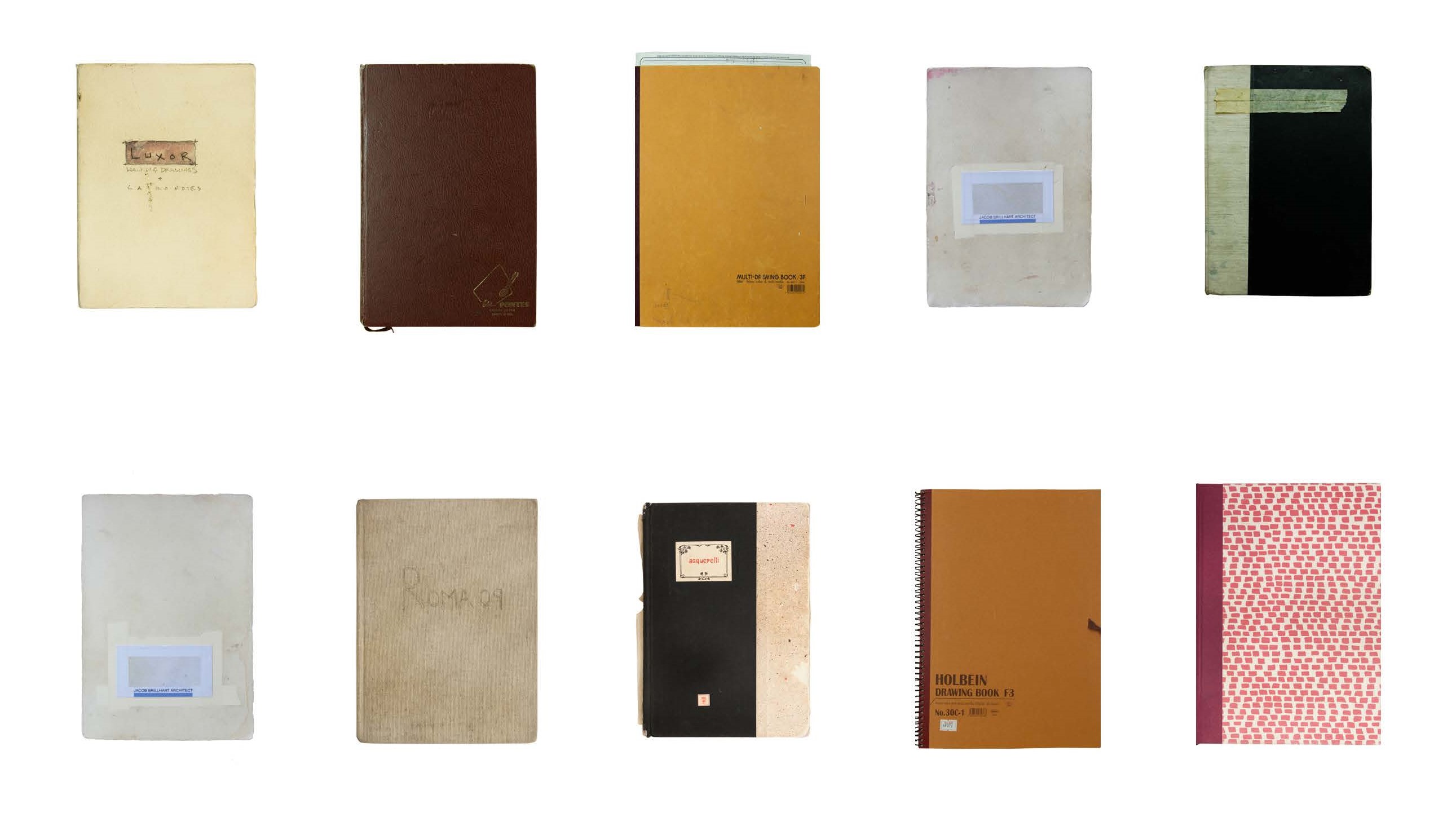

As for my own experiences -- to date, I have filled over 30 sketchbooks with more than 700 drawings and notes of architectural details, maps, people, buildings, objects, and urban spaces in cities around the world, including many of the same places where Corbusier stood almost 100 years earlier.

These personal “drawings on the road” have evoked an intensive physical and living architectural investigation of how I process and perceive information. In physically drawing what I see in situ, I have learned to analyze buildings, piece by piece, to understand their material nature and construction assemblies and how they are integrated: observing the thicknesses of each material; the details of how they are cut, fastened, and connected; whether the structure is revealed or hidden; and what they express tectonically. I’ve also learned to recognize the persistencies in architecture.

This self-imposed education serves as a spring point for design within my own office. With a working knowledge of those constant architectural principles that do not change, I am able to explore those other aspects of architecture that do change – such as new technologies, materials, fabrication techniques, construction assemblies, and representational media – aspects that make architecture present and transformative.

THE FIRST TRIP

Florence, Venice, Vicenza, Grenada, Madrid, Sienna, Rome

THE SECOND TRIP

Rome, Venice, Capri, Santa Marinella, Vicenza, Tivoli, Parma

THE THIRD TRIP

Amsterdam, Utrecht, Brussels

THE FOURTH TRIP

Rome, Paestum, Venice, Berlin, Athens

THE FIFTH TRIP

Tokyo, Kyoto, Istanbul

“A drawing needs to be going some place – it should have a direction. Like classical music, it builds up, then settles down and then revisits itself again. Musical notes have variety and slight variation in them. So does a good drawing. Stop finishing all your drawings, Jake.”

– Errol Barron

in a conversation we had sitting below the Acropolis (3/23/08)

– Errol Barron

in a conversation we had sitting below the Acropolis (3/23/08)